We are closing in on the final handful of weeks of the 2023 NASCAR Cup Series season, the stock car series’ 75th anniversary campaign. To celebrate, each week through the end of the season, Ryan McGee is presenting his top five favorite things about the sport.

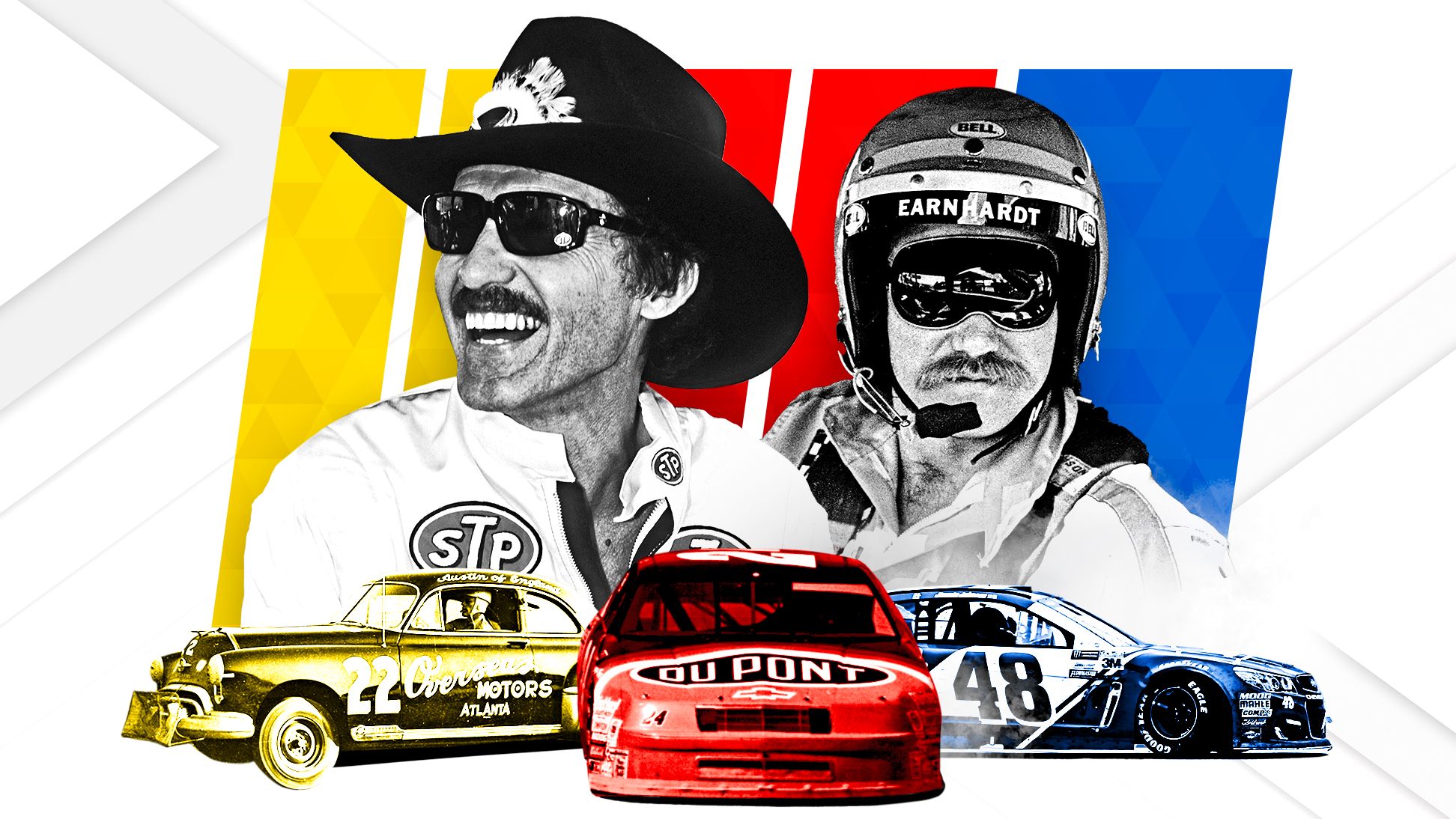

Top five best-looking cars? Check. Top five toughest drivers? We’ve got it. Top five mustaches? There can be only one, so maybe not.

Without further ado, our 75 favorite things about NASCAR, celebrating 75 years of stock car racing.

Previous installments: Toughest drivers | Greatest races | Best title fights | Best-looking cars | Worst-looking cars | Biggest cheaters

Five biggest what-ifs

For more than a month now we have presented our NASCAR 75 top-five greatest lists, and not surprisingly, they have all been met with a lot of questions. Particularly a lot of “Yeah, but what if … ?” questions.

Ah, what-ifs. There has never been a more confounding question ever asked. What if you hadn’t broken up with that one special someone back in high school? Or what if they hadn’t dumped you? What if you had taken your pal up on that investment scheme back in the day? What if Tom Cruise had said yes to the role of Iron Man and Robert Downey Jr. had never gotten the casting call?

It never takes much to ignite a breathless debate among NASCAR fans, but if you really want to kick-start a mind-bending conversation around a campfire in the Kansas Speedway infield this weekend, casually drop one of these topics on the group. Then don’t expect to sleep because you’ll be talking about it all night.

So, grab a Ouija board, a rearview mirror and a copy of Hugh Everett’s 1956 “Many Worlds” multiple-timelines thesis and read ahead as we present our top five biggest what-ifs in NASCAR history.

Honorable mention: What if Bill France Sr. hadn’t stealthily taken control in 1947?

In December 1947, nearly 40 bootleggers and businessmen gathered at the Streamline Hotel in Daytona Beach, Florida, to discuss the consolidation of stock car racing, attempting to bring the unruly patchwork of racers and sanctioning bodies under one operational umbrella. In those days, the sport was total chaos scattered across the United States with seemingly no chance of being simplified.

Enter the man who organized those meetings. Big Bill France, who worked the room like a skilled lobbyist from his hometown of Washington, D.C., and ultimately took charge. Seventy-five years later, his family still have their hands on the NASCAR steering wheel.

What if he hadn’t been so stealthily smooth, though? Would stock car racing still look like today’s short track racing, an entertaining but also endlessly scattered alphabet soup of organizational names and funky rules no one but hard-core racers know how to follow? Chances are, yes.

For more on that first meeting and how Big Bill seized control, read this piece from last winter.

5. What if David Pearson had actually raced for championships?

The Silver Fox ranks second only to Richard Petty in career wins (105) and poles (113), and his career winning percentage is a stunning 18%. Pearson rarely ran full-time schedules, though, choosing instead to focus on the biggest races with the biggest purses, as did the team with which he did the most damage, the Wood Brothers.

As a result, he made only 574 Cup Series starts, almost exactly half as many as Petty. In fact, the only three seasons he ran a full schedule — 1966, 1968 and 1969 — he won his three championships. So, how gaudy would his stats have been had he chosen to stick to the entire calendar? I asked him in 2011, when he was elected in the NASCAR Hall of Fame’s second class.

“If that word ‘gaudy’ means good, then yeah, pretty damn gaudy.”

4. What if Petty had signed with Hendrick Motorsports?

Speaking of The King, we all remember his 1984 campaign, when he earned his 200th career win in dramatic fashion over Cale Yarborough on July 4 at Daytona. What people don’t remember is that he spent that season driving for record executive Mike Curb because of financial troubles at Petty Enterprises. Curb’s situation wasn’t much better, and that win ended up being the final victory for His Royal Fastness.

What most people don’t know is that Petty was all but inked with brand-new team owner Rick Hendrick, a Charlotte car dealer who was getting into NASCAR. The deal fell apart at the last minute, and Hendrick signed Geoff Bodine, who wound up winning three races in 1984 and seven total with Hendrick.

What if Petty had been in that Chevy instead as Hendrick Motorsports rose to become the team Petty Enterprises had been? How many wins past 200 would he have earned?

3. What if Hall of Fame crew chiefs stayed with their Hall of Fame drivers?

Compounding Petty’s problems in 1984 was that he was without the crew chief who had called the shots for 188 of his wins and all seven of his championships, cousin and fellow NASCAR Hall of Famer Dale Inman. Inman left Petty immediately after they had won their seventh Daytona 500 together in 1981 and went on to win races with Dale Earnhardt and Tim Richmond as well as the 1984 championship with Terry Labonte.

It’s a common tale.

Ray Evernham parted ways with Jeff Gordon after they won three titles in four years and 47 races. Gordon won one more title in 2001 but never returned to his earlier dominance. Kirk Shelmerdine, elected to the Hall last year, won four titles with Earnhardt but abruptly left to pursue a driving career. Even Chad Knaus and Jimmie Johnson broke up in 2018 after seven Cups and 83 wins. Johnson never won again and Knaus won once with William Byron before Johnson and Knaus retired from full-time Cup racing in 2020.

2. What if Matt Kenseth hadn’t stomped the Cup field in 2003?

Back in the day with the longtime Cup Series points system in place, it was commonplace for drivers to celebrate clinching championships with races still remaining on the schedule, and mathematically we often had known they would win way before that. But in 2003, Kenseth not only essentially locked up the title early but did so while winning only one race all year, rolling into the season finale having cranked out 25 top-10s with only one DNF.

It was the final straw for NASCAR leadership, who responded by introducing the Chase format the next season, bolstering points for wins and carving out the last chunk of the schedule and calling it a postseason.

No matter how much the Chase/Playoff format has changed over the years, it has remained polarizing for fans and created a lot of “what if?” questions about who would have won Cups had the old format remained. (Spoiler alert: Gordon would be much happier with his trophy case.)

1. What if Earnhardt had survived?

In a sport where death can be the cost of doing business, the list of what-ifs when it comes to who would have done what is a long one.

3:04

Earnhardt Jr. recalls the day of his dad’s fatal crash

Dale Earnhardt Jr. remembers back to what the day his father’s fatal crash was like.

Earnhardt admitted many times that had Richmond, Alan Kulwicki and Davey Allison been able to continue their racing careers, then his record likely would have looked different. Since Feb. 18, 2001, though, when Earnhardt died on the last lap of the Daytona 500, not a day has gone by when those who knew and loved The Intimidator haven’t wondered what today’s NASCAR would look like if he were still around.

Would he have won an eighth championship after his resurgence in 2000 that saw him finish runner-up to Bobby Labonte? Would Dale Earnhardt Inc. now stand alongside Hendrick Motorsports and Joe Gibbs Racing as a juggernaut of the sport? Would his powers of persuasion over NASCAR brass have prevented moves like the Chase and stage racing, or would he have supported those changes?

On the flip side, would we have the crucial safety innovations implemented in the years since? Not a single driver has died since Earnhardt did.

I don’t know the answer to any of that. I just know I wish he were still here so we could have seen it for ourselves.

For more on this topic, go back to this in-depth series in 2021, written on the anniversary of Earnhardt’s death.